(Five minute read)

The truth is.

Limiting the damage requires rapid, radical change to the way the world works.

In this post I will lay out the true case for pessimism and the true case for (cautious) optimism.

“Is there hope?” is just a malformed question.

It mistakes the nature of the problem.

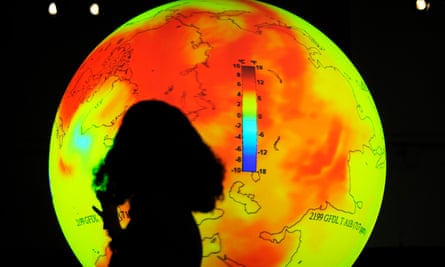

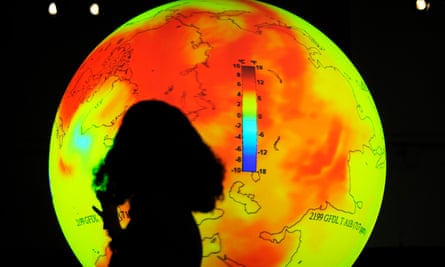

The atmosphere is steadily warming. Things are going to get worse for humanity the more it warms.

But there’s nothing magic about 2 degrees. It doesn’t mark a line between not-screwed and screwed.

We have some choice in how screwed we are, and that choice will remain open to us no matter how hot it gets.

Even if temperature rise exceeds 2 degrees, the basic structure of the challenge will remain the same.

It will still be warming. It will still get worse for humanity the more it warms. Two degrees will be bad, but three would be worse, four worse than that, and five worse still.

When temperatures reach 60c photosynthesis stops working and the need for sustainability becomes more urgent, not less. At that point, we will be flirting with non-trivial tail risks of species-threatening — or at least civilization-threatening — effects.

In sum:

Humanity faces the urgent imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, then eliminate them, and then go “net carbon negative,” i.e., absorb and sequester more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits.

It will face that imperative for several generations to come, no matter what the temperature is.

What are the reasonable odds that the current international regime, the one that will likely be in charge for the next dozen crucial years, will reduce global carbon emissions enough to hit the 2 degree target?

Can we restrain and channel our collective development in a sustainable direction. NO

For any hope of hitting 2 degrees, global emissions must peak and begin rapidly falling within the next dozen years. And they must continue rapidly falling until humanity goes net carbon negative sometime around mid-century or shortly thereafter.

That means developed countries must go negative earlier, to allow for a slower and more difficult shift in developing countries.

Accomplishing that would require immediate, bold, sustained, coordinated action. And, well … look around. Look at how things are going. Look at who is running things. Look at the established economic regimes of the last half-century. Is this likely to happen, not on your nelly

As Enno Schröder and Servaas Storm of Delft University write in their blunt and unsettling recent paper, “the required degree and speed with which we have to decarbonize our economies and improve energy efficiency are quite difficult to imagine within the context of our present socioeconomic system.”

The dominant climate-economic models used to generate scenarios showing how to hit the 2 degree target produce a few key common outcomes.

One is that they require an extraordinary amount of energy efficiency. The bulk of the reduction in demand for fossil fuels through 2040 or so, in most successful 2 degree scenarios, is accomplished by reduction in overall energy demand. It is only around 2040 that displacement of fossil fuel energy by zero-carbon energy takes over as the dominant driver of fossil fuel reductions.

For centuries now, the growth of economies has been tightly coupled with rising energy demand and rising greenhouse gas emissions — a one-to-one correlation, more or less.

In recent years, however, several countries have seen their economies grow faster than their emissions.

The world’s current economies are not capable of the emission reductions required to limit temperature rise to 2 degrees. If world leaders insist on maintaining historical rates of economic growth, and there are no step-change advances in technology, hitting that target requires a rate of reduction in carbon intensity for which there is simply no precedent.

Despite all the recent hype about decoupling, there’s no historical evidence that current economies are decoupling at anything close to the rate required.

In fact, it’s worth noting that the vast majority of scenarios used by climate policymakers take continued economic growth as an unquestioned premise. And they also accept that historical technology improvement rates will hold in the future. The question they basically answer: “How much can we reduce emissions while continuing to grow our economies at historical rates, with technology developing at historical rates?”

Put simply, if we are determined to maintain the economic status quo, we cannot possibly mitigate climate change, so we must turn to adapting to it.

We have to come to terms with the impossibility of material, social, and political progress as a universal promise: life is going to be worse for most people in the 21st century in all these dimensions.

The political consequences of this are hard to predict.

The choice is radicalism today or disaster tomorrow, and from all signs, humanity is choosing the latter.

The fight to decarbonize and eventually go carbon negative will last beyond the lifetime of anyone reading this post. That is true no matter how high the temperature rises. The stakes will always be enormous; time will always be short; there will never be an excuse to stop fighting.

All of this needs collective action and a strong directional thrust which ‘markets’ or ‘private agents’ alone are unable to provide.

But rapid change is not just possible in technology. It is also possible in politics.

In both domains, there are “tipping points” after which change accelerates, rendering the once implausible inevitable.

We are rarely able to predict those tipping points.

Relying on them can seem like hoping for miracles. But our history is replete with miraculously rapid changes. They have happened; they can happen again. And the more we envision them, and work toward them, the more likely they become.

What other choice is there?

It will take close to half a million years before a ton of CO2 emitted today from burning fossil fuels is completely removed from the atmosphere naturally.

The world militaries contribution to green house gases ( and I am guessing ) alone is bigger than the economic out put of the whole of the African.

It has been 30 years since the Rio summit, when a global system was set up that would bring countries together on a regular basis to try to solve the climate crises.

The ink was hardly dry on the Glasgow pact when the world began to change in ways potentially disastrous for hopes of tackling the climate crisis. Energy and food price rises mean that governments face a cost of living and energy security crisis, with some threatening to respond by returning to fossil fuels, including coal.

Despite pledges made at climate summit the world is still nowhere near its goals on limiting global temperature rise. The next summit will be on different as no one wants to carry the financial can.

(In previous post I have suggested the establishment of a Perpetual green fund by placing 0.05% commission on all activities that are not sustainable.) This could spread the cost of tackling the climate crises Fairley.

We don’t have time to have unquestioned assumptions.

The real truth is that the earth in its billion of years of existence ( with our without us) has gone through many climate change disasters and survived.

We on the other had only need a further temperature rise to join a log list of extinction.

All human comments appreciated. All like clicks and abuse chucked in the bin

Contact: bobdillon33@gmail.com

.